It is 2025, and Vincentians are preparing for what may well be the most significant general elections in our nation’s history. What lies at stake is either an unprecedented sixth consecutive term for the ruling party or a return to office for the opposition, who have not held the reins of governance in over two decades. In assessing this moment, it is only fair that we examine the past 24 years of both the ruling party and the opposition.

Over the last 24 years in government, St. Vincent and the Grenadines has seen remarkable development, despite the many challenges that have tested our resilience. To doubt that progress has been made is to ignore the visible changes across the country. Ask yourself this: would you truly want to return the country to the state it was in 24 years ago? Speaking personally, I cannot. That is not to say the opposition performed poorly during their tenure, but rather, the country has undergone significant transformation for the better.

When we look across the region, it is clear that we have come a long way—though we must admit we were late to the party. Still, we are moving forward. And let it be said: we do not compare ourselves with our neighbours to compete, but to learn. The progress of our sister islands should inspire growth in us, not rivalry. A simple glance at regional data would show that St. Vincent and Dominica are the only two OECS nations in the 20th century to secure, or be in the process of securing, international airports. That alone says much about where we are heading.

We must also acknowledge a geographical reality often overlooked. Like Dominica, St. Vincent has fewer flat lands, making development more challenging. This has played a part in why other OECS countries reaped earlier benefits from colonial investments—be it ports or early exposure to global tourism. Others had larger populations to leverage, and that too matters.

A lot has been invested in education over the years. While there is ongoing debate around the Education Revolution and its implementation, its successes are visible. Access to both secondary and tertiary education has expanded. More and more homes are celebrating university graduates—something rarely seen under the previous administration. There is more that can be done, but much has already been achieved.

That said, one cannot ignore that, despite a few salary increases, many feel that the cost of living offsets any benefit. On paper, progress is evident. On the ground, the reality feels different. Still, there is promise, and if the ruling party is given the chance to continue, we can only hope that the plans already in motion will bear greater fruit.

Our tourism sector continues to climb to new heights. Each season brings more airlines, more rooms, and greater exposure. The Sandals development has lifted the standard, and even members of the opposition have gone on record in Parliament acknowledging that tourism is on the right path.

However, the government’s performance with the private sector leaves much to be desired. While there are programs aimed at supporting private enterprise, political bias continues to affect how resources are distributed. Heavy taxation remains a burden, though signs of progress in other sectors offer hope for more balanced growth. Agriculture and fisheries, for example, show signs of revival—but more is needed. Effort alone is not enough; execution is key.

Now, let us turn to the New Democratic Party (NDP), which has spent the last 24 years in opposition. While they have not held power, they have not been idle. Over the years, they have pushed for several meaningful policy proposals—such as tax relief for small businesses and various ideas aimed at improving livelihoods. These contributions must be acknowledged.

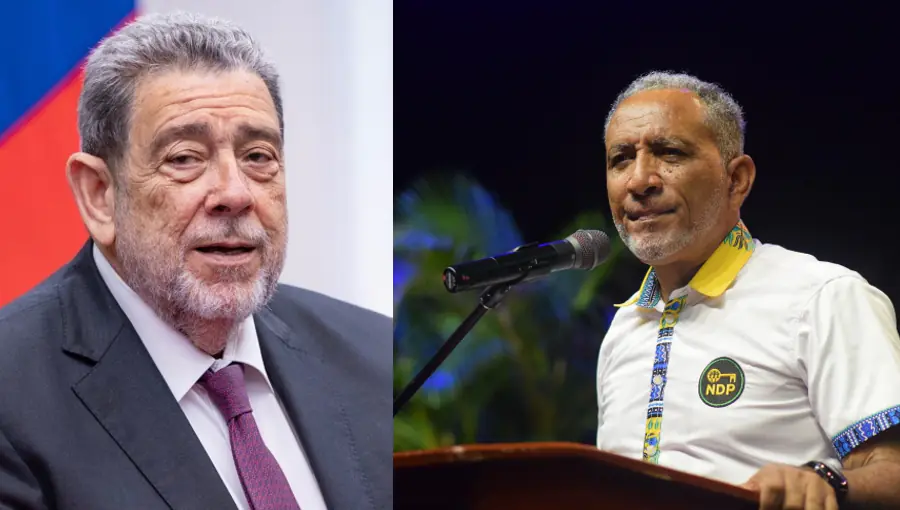

At the same time, the NDP continues to have opportunities to convince the nation that they are ready to govern—but at every election, they lose footing at the polls. A consistent trend has emerged where each cycle, they bring a new face to the forefront—selling that individual as the brightest hope and next in line to be Prime Minister. From Bramble to John to Shallow, this tactic has only served to weaken the image of the actual party leader, casting doubt on their internal confidence and long-term vision.

The 1998 election reflected a clear national shift—so much so that even Arnhim Eustace barely retained his seat by a mere 27 votes. On the other hand, 2020 did not indicate any such shift. While the NDP won the popular vote by a slim margin, voter apathy played a major role. Many Vincentians simply chose not to vote at all rather than cast their ballot for the opposition. That alone speaks volumes about the level of confidence—or lack thereof—the electorate holds in them.

The NDP has also struggled with consistency and presentation. Too often, they appear erratic, lacking the discipline and unity expected of a government-in-waiting. At times, they resemble a child with a weapon turned upon themselves. That is not what inspires national confidence. If a change is to come, they must present themselves not as the “other” option, but as the better one.

The electorate is not foolish. They will not vote out of blind loyalty or sheer frustration—they vote for who they trust. And while the NDP has tried to replicate the strategies that once worked for the current Prime Minister, the context has changed. The party has at times mixed truth with falsehood in their attempts to sway public opinion, and in doing so, may have lost credibility. Being in opposition is not about blindly opposing; it is about holding government accountable with reason and vision.

Take, for instance, the international airport. The NDP went to great lengths to cast doubt on it, even writing to international bodies. They opposed constitutional reform and were hesitant to support numerous developmental projects. Ironically, in the last elections, they won the popular vote by just 485 votes—yet lost another seat in Parliament. Numbers do not lie. When the ULP won the popular vote but lost the election in 1998, they did so by over 4,500 votes and still retained significant parliamentary strength. Context is critical.

The NDP must also be careful not to oversell themselves as a party that can curb all crimes, fix the economy overnight, and have everyone employed in short order. These are complex challenges. Offering unrealistic expectations sets them up for failure. Additionally, their over-reliance on the Citizenship by Investment (CBI) programme as a supposed cure for all problems has only contributed to the perception of laziness—voiced now even by their own supporters.

It has been 24 years—ample time to develop a vision that inspires confidence. Yet the party continues to fall into old patterns. The ghost of 1998 still haunts their strategy, even when today’s political landscape demands something fresh, measured, and credible.

As the next election approaches, Vincentians must ask themselves an important question: Who is best positioned to take us forward? We may be going in the right direction, but it is time to decide who should continue steering the way. The decision lies with us, and come election day, we will answer.