WEST INDIES ONE-DAY CRICKET CHAMPIONS, JUNE 1975

FIFTY YEARS AGO

Fifty years ago on June 21, 1975, the West Indies defeated Australia by 17 runs in the closely-contested finals, at Lord’s, England, of the inaugural One-Day International Cricket Championship. Accordingly, the West Indies became the first One-Day Cricket Champions. There has been, thus far, a deafening silence from Cricket West Indies (CWI) on this historic achievement; and no plans have been unveiled by CWI to commemorate it in any meaningful way or at all.

It is the same story with the 60th anniversary of the West Indies’ status as unofficial test cricket champions at the conclusion of their history-making triumph over Australia in the test series in the West Indies which ended on May 17, 1965: Silence from CWI as though our glorious history is of no moment whatsoever.

Three weeks or so ago, I spoke and wrote about the 60th anniversary of the 1965 victory and its significance, then and now. CWI has remained comatose, unresponsive. And they are sleep-walking through the 50th anniversary of the 1975 triumph. Perhaps CWI’s leadership has no sense of our cricket history and its existential importance to our current cricketing condition and our cricketing future. Or perhaps, CWI is too busy chasing after ephemeral passport-selling money or gingering up support across some countries in the region for the illusory pot of gold from the dangerous, addictive video slot machines of gamblers. Or maybe they are too pre-occupied with dreaming in India in a further marginalisation of West Indies cricket, show-boating without substance, for our players and our cricket. Or CWI is just plain lazy, lacking in creative ideas as to the way forward, most assured about that which they are most ignorant; insufferable men, pompous to the core, dressed in their brief authority, who play such fantastic tricks before high heaven as to make angels weep.

THE 1975 CRICKET WORLD CUP

The 1975 Cricket World Cup, the first-ever One Day International (ODI) Cricket championship, was organised by the International Cricket Conference (ICC). It took place in England, between June 7th and June 21st, 1975.

The tournament had eight participating countries: The six Test-playing teams at the time (Australia, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, the West Indies) and the two leading Associate cricketing nations (East Africa and Sri Lanka). Each match consisted of 60 overs per team and with traditional red balls; all matches were played and ended in daylight. Night matches, under lights, had not yet come into vogue.

Both Australia and the West Indies made it to the finals through the knock-out and groups stages.

THE FINALS

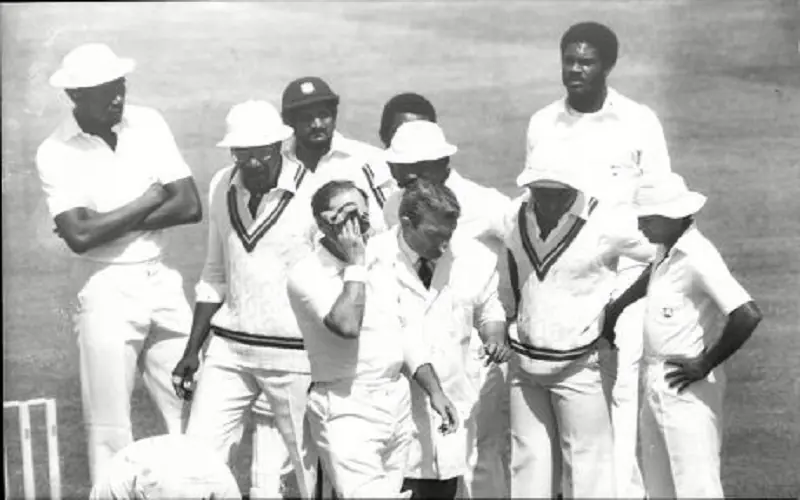

One June 21, 1975, at Lord’s, Australia and the West Indies displayed their cricketing skills before a crowd of 26,765. The West Indies XI for the finals comprised: Clive Lloyd (captain), Roy Fredericks, Gordon Greenidge, Alvin Kallicharan, Rohan Kanhai, Vivian Richards, Keith Boyce, Bernard Julien, Deryck Murray (wicket keeper), Vanburn Holder, and Andy Roberts. This multinational squad, playing under the integrative rubric of the West Indies since its official entry into test cricket in 1928, consisted of: Four players from Guyana; three from Barbados; and two each from Antigua and Barbuda, and Trinidad and Tobago, respectively.

The Australia XI comprised: Ian Chappell (captain), Allan Turner, Ric Mc Coster, Greg Chappell, Doug Walters, Rodney Marsh (wicket keeper), Ross Edwards, Gary Gilmour, Max Walker, Jeff Thompson, and Dennis Lillee.

Australia won the toss and asked the West Indies to bat first. The West Indies scored 291 for eight wickets with Julien and Holder as the not out batsmen; Andy Roberts at Number 11 in the batting-line up, did not bat. The West Indies’ run rate was a commendable, though modest by current standards, 4.85 runs per over.

The outstanding batsman for the West Indies was Clive Lloyd with a top score of 102 runs. Kanhai made 55; Boyce 34; and Julien was not out on 26. Lloyd’s 102 were scored off 85 balls, a splendid strike rate of 120, with 12 fours and two sixes. The other batting stars were underwhelming in their performances: Fredericks, 7 runs; Greenidge, 13 runs; Kallicharan, 12 runs; and young Vivian Richards, 5 runs.

The most effective Australian bowler was the fast-medium Gary Gilmour (5 wickets for 48 runs off his allotted 12 overs). Jeff Thompson was a problem for the West Indies (2 for 44 off 12 overs). The usually dangerous Lillee bagged one wicket for 55 runs off his 12 overs.

Australia’s turn at the crease produced 274 runs all out, off 58.4 overs. The Aussies’ top-scorer was Ian Chappell with 62 runs off 93 balls. Other commendable scores came from Turner (40 runs off 54 balls), Doug Walters (35 runs off 51 balls), Ross Edwards, (28 runs off 37 balls), and Jeff Thompson, batting at number 10, a flashy 21 runs off 21 balls.

The best West Indies’ bowler was the fast-medium Keith Boyce with 4 wickets for 50 runs off 12 overs. The only other bowler who took a wicket was Lloyd (1 for 38 runs off 12 overs). The remaining three bowlers (Roberts, Julien, Holder) did not take a wicket, but Roberts bowled tightly (45 runs were scored off his 11 overs). Five Australian batsmen lost their wickets through the run-out route. Viv Richards, brilliant in the field, was responsible for the run-outs of three outstanding batsmen (Turner, Ian Chappell, and Greg Chappell).

This was Clive Lloyd’s ODI! He was the universal choice as “Man of the Match”: He scored the only century and in quick style; he was the most economical bowler in the game; and he assisted Viv Richards in running out Ian Chappell who was well-set on 62 runs. Moreover, his captaincy of the West Indies was magnificent. We continue to thank Clive for his immense contribution to the victory in 1975, and for his overall, heroic work for our cricket; undoubtedly, a living legend worthy of emulation and a lifting up, always.

IMPORTANCE OF HISTORY

In 1994, thirty-one years ago, I authored a book entitled, History and the Future: A Caribbean Perspective. I began it with these opening two paragraphs of continuing relevance:

“The very mention of ‘history’ frequently invites derision even by those who ought to know better. The pioneering American entrepreneur and engineer, Henry Ford, is as much known for his signal contribution to the motor car industry as for his off-hand comment that ‘History is bunk’. This aphorism is often quoted approvingly by the uninformed in an attempt to debase the study of history ——.

“This debasement or relegation of history is not merely as a consequence of the limited employment or economic prospects for historians in modern industrial or industrializing societies. The cause is probably more deep-rooted. History, like allied disciplines such as political science, sociology, economics and philosophy, raises uncomfortable questions which the ruling powers of society would rather not countenance.”

I, then, in a preliminary summation, offered a perspective on the importance and relevance of history in the following three paragraphs:

“Yet, history has walked with man since the beginning of time. It is the study of time in motion as man interacts with man and they with their environment in their quest to improve the quality of life. It is the study of man as he has evolved in a changing society. This is an exercise of enormous significance to contemporary man’s effort to improve upon his predecessors’ contribution in mastering and in making for himself, his family, a better and wholesome life. Much of this study may be dull, but it surely does not merit the ridicule which Alexander Pope heaped on historians in his lines:

‘To the future ages may the dullness last,

As though preserv’st the dullness of the past.’

“Of greater poetic insight in the process of evolving time, changing man, and the necessity of history is the Vincentian Daniel Williams’ verse in his poem ‘We are the Cenotaphs’:

‘We are all time,

Yet only the future is ours

To desecrate.

The present is the past,

And the past

Our fathers’ mischief.’

“To avoid a desecration of the future, to glean a proper appreciation of the present and to escape the folly of our fathers’ mischief, the study of history is necessary. As Arthur Marwick tells us in his celebrated volume, The Nature of History:

‘It is only through knowledge of history that a society can have knowledge of itself. As a man without memory and self-knowledge is a man adrift, so a society without memory (or more correctly, without recollection) and self-knowledge would be a society adrift.’ ”

I urge everyone, especially the officialdom of Cricket West Indies, to heed the proffered advice.

CWI ADRIFT

Cricket West Indies (CWI) is too important for our region to allow its continued drift. Its current leadership, self-evidently, is incapable of arresting the jetsam and flotsam of the wreck that is official CWI. We the West Indian people, the clubs, the players, the national cricket entities, and the regional governments — all the relevant stakeholders — must save our cricket, despite the weight of the overbearing encumbrance of CWI, propped up only by the international recognition of the ICC and some dreamers in India, and turn its setbacks into advances, consolidate its successes, and restore this existential body and mind known as West Indian cricket to its former glory and standing.

CWI is busily engaged in the minutiae of managing this or that, in the absence of any transforming strategy, while regressing in every material particular. CWI’s descent is predictably accompanied by tiresome, incoherence, stylising facts in search of a theory of explanation for its stagnation and regression; the optic equivalent of an exasperated blind man (CWI) in a dark room, knocking over chairs, looking for a moving dog that does not bark or bite. Thus, expect nothing of any consequence, for the better, from official CWI.

Let us be clear: Hustling on the side to sell passports and citizenship of this or that country or proselytizing for crumbs from youth-destructive video slot machines or dreaming as gamblers, will not lift cricket in the West Indies. CWI does not as yet realise, and the debilitating, ideological class perspective of the managerial petit bourgeoise, aligned with cricket imperialism and monopoly capitalism overseas, will never realise, that the answer to its woes lies in the genius of our people in whom flourish visible and hidden resources and “rationalities” available for sustainable national development, including that of cricket. In this paradigm shift, transformative leadership is vital. That is plainly absent from CWI. As Lloyd Best used to say: “To be sure, they are busy; busy doing nothing.” CWI is fast becoming an irrelevance save for its formal international nexus with ICC; fundamentally, it is a brake on cricket’s further advance. We the people must rescue our cricket. This is my clarion call to all relevant stakeholders outside official CWI.

The predecessor to CWI, the West Indies Cricket Board of Control (WICBC) was, for most of its history, owned and controlled as a “plantation” by the regional planter-merchant elite in alliance with the ICC headquartered at Lord’s, England, controlled by the English aristocratic and banking elites. CWI, a private company registered in the British Virgin Islands, is now operating as a run-down “colonial plantation” manned by the petit bourgeois professional class, in a junior alliance with the ICC, currently headquartered in Dubai and dominated by the moguls of Indian cricket and monopoly capitalism.

The old WICBC was never, and the new CWI is not, legally owned by the people of the region. Regional cricket officialdom, as private entities, with external alliances, has never been able to square the circle shaped by a central contradiction: A private entity seeking to manage a public good (cricket) while squatting on neo-colonial premises. In earlier times, for various reasons, regional cricket officialdom, despite itself, benefitted from the mass cultural enthusiasm for cricket as a force for national liberation. The modern CWI overseas cricket, with hugely reduced popular enthusiasm for the game, under the hegemony of an ICC dominated by Indian cricket imperialism and global monopoly capitalism. In effect, the men in the old WICBC were largely planter-merchant types on horseback wearing white cork-hats. The new CWI with petit bourgeois bureaucrats in SUVs, wearing metaphoric brown cork-hats. Their external allies are different. And the people for whom the game still mean something are, by and large, by-standers. The situation is dire. Revolutionary changes are required; only the people, properly-led with a transformation plan, can take us out of the current many-sided malaise which besets our cricket in the West Indies. Understand this: There is a dialectical interconnection between what takes place within the boundary ropes and what occurs beyond the boundary; the dialectics revolve around the material, the ideational and the existential. And the dialectics are played out through history in its joinder with the contemporary condition. The petit bourgeois bureaucrats in CWI do not grasp all this!